These events took place from Monday, October26th to Friday October 30th.

Forward

For the last two months, my search for a pain professional who accepted Medicaid and was willing to work with my autism medication regimen had resulted in my being disbelieved, belittled, insulted, and dismissed at every turn. During this time, my pain was poorly managed—if at all—and I dealt with constant anxiety. By mid-October, I was down to rationing the last few doses of the only pain medication I had left that didn’t interfere with my autism prescriptions.

The light at the end of this dark tunnel was a long-overdue cervical fusion surgery scheduled for Tuesday, October 27th at 11 AM. The surgeon would be able to prescribe medicine to handle the post-surgical pain, with the promise of reduced pain over the long-term.

But that isn’t what happened. This is what happened instead.

Monday, October 26, 2020

The day before my surgery was a mad scramble of emails, laundry, and housekeeping to prepare for being out of commission for a few days. My sister, TNC [Takes No Crap] Ape, had come into town Saturday to be my pain advocate and was bustling around on my behalf, learning where things were, how things were done. Captain Ape arranged to have a break from work to be our chauffeur. We had planned and for prepared everything, down to the smallest detail, but I was still so anxious I couldn’t sit still. “I have a bad feeling about this,” I confided in my sister, in Captain Ape. They offered reassurances that, while appreciated, were not able to quell this burgeoning dread lodged in my stomach.

My anxiety wasn’t completely unfounded, although I didn’t realize it at the time. A lack of notification from the surgeon’s office that my surgery time had been changed from 11 AM to 7:30 AM, which I never would have known about if the nurse hadn’t mentioned it during pre-op testing, set me on edge. Distracted and tense, I forgot I had a cell phone (actually, this happens a lot) and missed a late evening call and voicemail from my doctor’s office.

Tuesday, October 27, 2020

The day of the surgery, Captain Ape dropped off TNC and me at the hospital at 5:30 AM, two hours before the surgery, as instructed. But when we checked in at the COVID testing station, they couldn’t find me on the list of admissions. They let us through anyway, but upstairs in the surgery waiting area, the nurse escort for surgical patients also did not have me on her list. She told us to wait there while she made some calls.

She came back fifteen minutes later. “We couldn’t get a hold of your doctor” she said apologetically. After a pause, she added. “I’m sure he’s on his way.” I knew she was lying, but I clung to the hope that she was right. TNC and I sat down to wait.

After a half an hour, the nurse let us know she found me on the list—for 11 AM. I was too angry to respond and couldn’t stand to be in that waiting area another second. I abruptly got up and strode out, leaving my sister scrambling to catch up with me at the elevator. “So we’re leaving?” she asked.

“Hell yes, we’re leaving,” I snapped. Once we got outside, my sister called Captain Ape to come pick us up so we could wait at home until it was time to come back.

It was only then that I discovered the missed call and voicemail from the doctor’s office the night before. The message stated that the radiologist had “filled out a form incorrectly” and they had had to resend it, and they had moved my surgery back to 11 to give the insurance company time to send back confirmation.

I leapt from annoyed to furious, about the pointless loss of the three hours’ sleep, with myself for not checking my phone. I remembered I had assumed that no phone calls of importance would show up the day before my surgery, or at least, nothing that couldn’t wait another day or two. Changing my surgery time the night before? Yeah, no, not on the list.

We got back to apartment around 7 AM, but I couldn’t get through to the surgeon’s office until they opened at 8. Once I did, the surgeon’s assistant repeated what was on the voicemail, saying the radiologist had messed up the form, that they had corrected it and sent it back, and that they were just waiting for confirmation from the insurance company to proceed. I was still to plan for surgery at 11.

An hour went by. I called my surgeon’s office again but no one answered. I left a message in which my tone of voice was not well managed. Captain Ape had slipped out at some point; he returned with Starbucks. I wasn’t supposed to have anything to drink, but I was thirsty and my willingness to cooperate had declined precipitously. I gratefully accepted the decaf Americano (my favorite) and sipped on it while I waited. Another hour passed.

My call was finally returned a little after 10 AM. This time, the assistant admitted that, rather than a form mix-up, the insurance company had rejected the procedure as not medically necessary, and what had actually happened was that they had entered an appeal but hadn’t heard back. She insisted that the preauthorization had been approved “this past Friday” and that none of this “made any sense.” She then asked if she could reschedule my procedure for two or three weeks down the road.

I had been planning for this surgery—no, I had been counting on it—for over a month. I was looking forward to a few days off from worrying about work, about school, about taking care of the apartment and the pets, about where my next prescription was coming from. It was all going to be taken care of for me, by TNC and Captain Ape, by the surgeon who could hopefully fix my neck and prescribe post-surgical pain medication. There was even a possibility that, once I healed from the surgery, my pain would be lessened significantly.

And then, less than an hour before it was supposed to happen, it was all yanked out from under me, just like that, in a single instant. It was so sudden, so devastating, I could barely breathe. I wanted to scream, to cry, to hit something, to throw something.

The surgeon’s assistant then had the audacity to ask if they could just “bump” my procedure to a few weeks from now, like moving a surgery was as simple as changing a meeting date in your phone.

“No, I can’t do this in a couple of weeks.” I snapped. “I already had to push back work and school obligations to make room for this. My sister had to put in for time off over a month ago. If we don’t do this now, I won’t be able to do it until December.” My control over my emotions, already tenuous, slipped even further. I struggled to keep the tears from coming.

The surgeon’s office had been lying to me since the day before, stringing me along, until the god from the machine they were expecting failed to show up. I was expecting an apology, some accountability, maybe even some sympathy. None was offered.

“Well, if we could do Friday, would that be OK?” the assistant asked. I mouthed “Friday?” to TNC Ape, who nodded, and told the assistant that, yes, I could make that work.

“Well, we’ve appealed the decision and we’ll call you back to reschedule as soon as it goes through.” she said.

I was unable to keep the tears back any longer. “OK,” I mumbled softly.

After a long pause, she said “Sorry about all this.”

I was afraid if I tried to talk I would start sobbing in earnest. “Mm-hmm.”

“So we’ll call you back soon.”

“Mm-hmm” I hung up and fell apart.

My sister came over to the couch. “What’s going on? What happened?”

“The surgery isn’t happening.”

“Isn’t happening today or isn’t happening ever?”my sister asked.

“I don’t know. They don’t know. Nobody knows.” I don’t remember what she said after that; I was crying too hard to hear her.

After a few minutes, I crawled into bed, my phone next to me on the pillow on the off chance that the surgery still might go through, and cried myself back to sleep.

The phone rattled me awake a little while later. “Hi there, this is the __________ hospital. Is this Ms. Ape?”

“Yes.”

“We just wanted to let you know that the insurance rejected your claim for being out of network.” Wait, what?

“No, my doctor’s office told me it was because it wasn’t medically necessary.”

“Well it says here you’re out of network. That’s all we know, ma’am.”

“OK. Thank you,” I responded. I hung up and went back to sleep.

I slept for a few hours, ate, and started making phone calls. I called my Medicaid caseworker, who was sympathetic but said there was nothing she could do—they only managed eligibility. They didn’t have any control over whether the provider authorized something or not.

I moved on to the insurance company’s customer service line, which was littered with menus for things I didn’t need and forced me to listen to their COVID preparations nearly a dozen times. The system kept dumping me back to previous menus or disconnecting me as I searched for the right options. The first person I got a hold of at told me I was in the wrong department and that I had to call back. Finally, after so many failed attempts I lost count, I managed to reach a human in the authorizations department. I explained what had happened, again fighting off tears, and asked if there was anything I could do to move things along.

The person on the phone pulled up and scanned through my account. After a few moments, she said the procedure had been rejected as not medically necessary and that it was being appealed, and that the appeal process took up to 30 days.

30 days? I forged ahead anyway. “So why did the hospital say I was out-of-network?”

“I don’t know anything about that. It just says here that it was denied as not medically necessary and is now under appeal. There’s nothing else you can do.”

I thanked her, hung up, and started sobbing again. I didn’t know who else to call, and even if I did, I was not up for yet another “sorry but I can’t help you” rejection. I gave up for the day. I don’t remember eating dinner. I don’t remember going to bed. I only remember I woke up crying in the middle of the night and that it took two hours to get back to sleep.

Wednesday, October 28, 2020

I was still red-eyed and exhausted the next morning, but after copious amounts of coffee, it was back to the phone. First, I called another surgeon I’d had a consult with the earlier in the month. He’d been kind and understanding about my condition, his office had an efficient and compassionate staff, and with any luck, maybe he would take my case and I could still get the surgery sooner rather than later. His office scheduled me an appointment for the next day, Thursday, October 29th.

As no pain medication was in the offing, I temporarily gave up on my search for a Medicaid- and autism-accepting provider and called back my original pain management practice, the one I had been seeing before I lost my health insurance, in hopes of getting enough medication to allow me to function until my surgery came through (or didn’t).

When I told the scheduler I would run out of medication before the end of the week, she miraculously found an appointment for me for Friday, October 30th. I would have to pay out of pocket, but I didn’t care. What had happened this week had left me so exhausted, traumatized, and desperate that I didn’t have any bandwidth left to think about anything else.

Thursday, October 29, 2020

Thursday, I drove to the surgeon’s office only to find out that I was at the wrong facility. “But they said it was in A_____ when I made the appointment,” I insisted weakly. Another staff member responded, “Oh, the S_______ office is also in A_____.” Notwithstanding how ridiculous that was, this wasn’t the first time something like this had happened to me; being autistic means you tend to miss “obvious” things and your assumptions are often wrong. I didn’t like it, but I was used it, and normally, I would have just handled it.

But that day, still drained from the previous days’ events, I didn’t have enough energy to deal with another setback. In fact, I didn’t have enough energy to summon any response at all, appropriate or otherwise. I just stood there, frozen, at a loss for what to say or do next. The other office just wasn’t going to happen; there was no way I’d be able to interpret a new set of my phone’s GPS instructions. Even just rescheduling felt like more than I could handle.

The receptionist saw the look on my face, or perhaps the lack thereof, and told me to wait a moment while they called the S_______ office and got the surgeon on the phone. Once they did, they relayed that the surgeon said he would not perform the surgery; he didn’t think it would help my pain, which he asserted was atypical for the type of damage I had.

Yet another rejection. My heart sank, and tears started to well up again. I held myself together—barely—long enough to thank them and get back to my car.

And then I started crying again. There was nothing else I could do. The grim reality of my situation, that the surgery wasn’t going to happen any time soon, if at all, finally set in. I sobbed the whole drive home.

Friday October 30, 2020

The pain appointment on Friday had the distinction of being the only interaction with a medical professional that resulted in a positive outcome that week. In fact, it was the only positive interaction I’d had with anyone in the medical community since before my insurance had run out three months before.

I briefly brought the NP up to speed on what had happened with my surgery. Then, I explained what had been going on with my search for a pain practice that accepted Medicaid and how dismissive those I’d tried had been about my autism. I stressed that medications that interfered with those I took to manage my anxiety and sensory sensitivity were off the table. I said that I understood that this meant diverting from usual protocols, but that I wasn’t the usual patient.

She nodded, echoed what I said back to me (another first), and scanned through my file on her laptop. “This much short-acting medication, you’re right, it’s not what we would normally prescribe, but it looks like in your case we have to throw the book out and just go with what works. For now, let’s just put you back on your regimen from before.”

I nodded. “OK. Thank you. That would be wonderful. Thank you.” She sent my prescriptions to the pharmacist and I picked them up later that afternoon.

But by then, I was completely used up. I never got those days off, from worrying, from advocating, from dealing with all the indignities one suffers at the hands of the American health care system. Instead, I’d had the week from hell followed by being unceremoniously dropped back where I was before, to a life inscribed by pain and anxiety, back to being disbelieved and dismissed, with medication that barely helped and a backlog of work.

Back into that dark tunnel, but with one difference. The light I had been working towards was gone.

Afterward

While I was fortunate to finally get back to my original pain treatment protocol, the physical damage resulting from two months of anxiety, loss of sleep, and little to no pain control, plus a week of extreme stress, was not so easily undone. My pain remained intense and unrelenting for a week and a half while the medications built back up in my system. It has been over two weeks and it is better, but it remains worse than it was before.

The psychological fallout took its toll, as well. The week after the surgery I was a zombie, unable to concentrate, unable to write, forcing myself to do my chores through a mental exhaustion that was almost palpable, and sleeping ten or more hours a night. What had happened to me was so unbelievable, so cruel, I couldn’t get past it. I hovered near tears for days, trying to process, trying to find something positive about it, and failing at both. The surgeon’s office has yet to call me back. If the procedure isn’t approved, they probably never will.

Two Weeks Later

Just when I thought the surgeon’s office could not have possibly screwed this up any worse, I got a packet a couple of days ago from the insurance company about my case, with copies of what the surgeon’s office had sent them for the preauthorization, authorization, and appeal.

For posterity, the surgeon’s office had led me to believe that the that the denial was the radiologist’s fault, and that both the denial and appeal had occurred Monday, October 26rd.

The packet, however, told a different story. The real story.

First, my preauthorization went through on Monday, October 19th, not Friday, as the assistant had claimed, and included a report of severe neck and upper back pain, an affirmation from a second surgeon that surgery was strongly recommended, and a diagnosis of encroachment leading to nerve impingement in the C5-C6 vertebral space.

The authorization did not contain any of those items, but that wasn’t the worst part. The worst part was the date, of both the denial and the appeal, as indicated by the dates on the faxes the office had sent. It wasn’t Monday, October 26th.

It was three days earlier. It was Friday, October 23rd.

The office had known about my denial since Friday afternoon and didn’t say a word to me about it for three days.

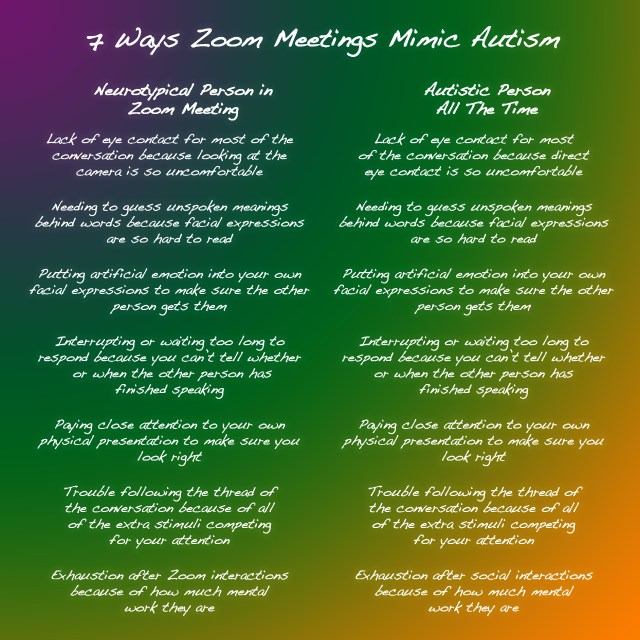

Three days. It may not seem like much, but for an autistic, three days to get used to the idea that my surgery might have to be postponed would have made such a world of difference that words fail to encompass it.

And here’s where people’s total ignorance about autism is especially poignant. Change is extremely difficult for autistics, exponentially more so than for neurotypicals. We need time to mentally prepare for changes, even positive ones. Those three days would have completely altered this experience for me. I would have been upset at first, yes, but by Tuesday, I would have been prepared for a possible negative outcome. To deny a normal person that time to adjust was already misguided, at best. But to deny it to someone on the spectrum? It was downright cruel.

As of this writing, the surgeon’s office has yet to own up to a single mistake. They changed my surgery time weeks before my surgery and didn’t tell me. The claim was denied and they didn’t tell me. The reason for the denial was due to their own failure to include the right information, and they didn’t admit to that, either. Even when they told me the “truth” about what happened, that had been a lie, too. There has been no formal apology, no sympathy for what they put me through, not a single indication that they felt in any way responsible for what had transpired.

It remains to be seen whether my insurance will or won’t approve the surgery. I went ahead and sent in a patient appeal, which included the things the surgeon’s office had left out of their October 23rd materials. Even if it does get approved, though, I have no idea who will perform the procedure. Certainly, the practice that screwed up the authorization, failed to notify me of a denial they had known about for days, and has yet to be straight with me about what actually happened, is not an organization I trust to be accountable for my surgery and aftercare.

At this point, I’m not sure when I’ll have the surgery, or even if I will have it all. And there is no next step, no Plan B. My experiences since my health insurance ran out strongly suggest that, even among the few medical practitioners who accept Medicaid patients, the number of them who actually care about Medicaid patients is vanishingly small. To most of them, I’m just a statistic, a box to be checked, someone they could do the bare minimum for so they could get back to the patients that made them money.

Even now, over two weeks later, I’m still exhausted, mentally, emotionally, physically. I don’t want to do this any more. I don’t want to be this any more. I’m tired of spending hours on the phone, having to expend energy I don’t have to perform my neurotypical persona, only to be told, over and over, by everyone I call, that they can’t help me.

And this is about more than just last week. I have endured three months of being invisible, my concerns unheard, my problems unsolved, my well-being unattended. There doesn’t seem to be any space in the world we live in for people like me. I know I should keep pushing and advocating for myself and those like me but I’m tapped out. I wish I could just sleep and eat and watch TV, and not have to take care of anyone or anything any more, even myself.

But that’s something else that won’t ever happen.